From Soviet Concrete to Urban Ideal

How Poland engineered 15-minute cities decades before the concept went mainstream—and why we abandoned socialist neighborhoods before rediscovering their value.

SOCIETYCITIESCLIMATE

Ewa Braniecka

11/1/20255 min read

Poland had built "15-minute cities" decades before these became a modern urban innovation. We simply stopped celebrating them.

What I Overlooked At Home

Growing up in Poland but later living abroad, I was convinced that everything foreign and international was automatically better. Paradoxically, it was while walking the calm, transit-rich streets of Helsinki and Copenhagen that I came to appreciate my own hometown, Kraków.

At its outskirts lies Nowa Huta. Its architecture was designed to embody 1950s communist ideology of "people-first," prioritizing the working-class's needs for decent living conditions, proximity to services, and community facilities. While it was implemented within a highly centralized and politically controlled system, its urban planning principles were prescient of what we strive to build today: 15-minute districts where residents can access all essential services within a short walk or bicycle ride.

Why does this matter? Because the 15-minute city concept addresses urgent contemporary challenges like reducing car dependency and emissions, improving public health, and strengthening local communities.

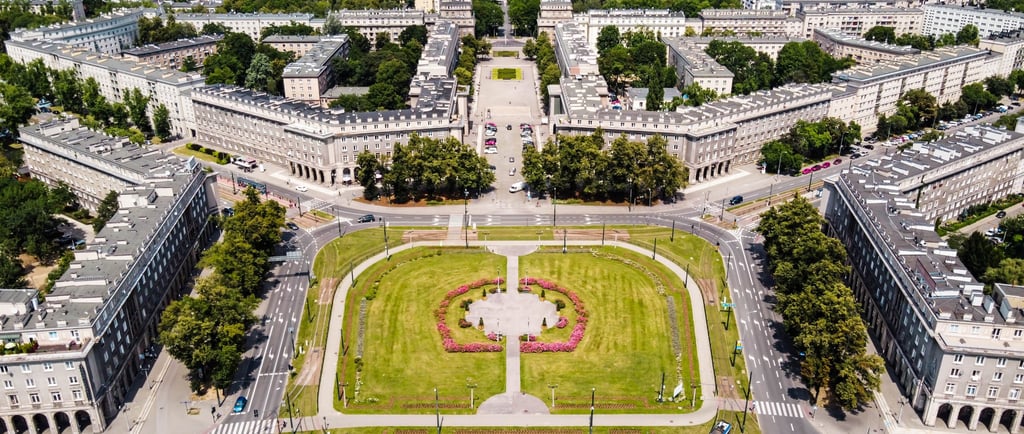

Nowa Huta district, Kraków

My Family's Choice: Then and Now

While researching this piece, I spoke with my mother, who lived through Poland's rapid modernization and privatization in the 1990s. She reminded me of our time in Osiedle Widok, a large housing estate built in the 1970s in western Kraków. Five of us were crowded into a small apartment, under the scrutiny of unfamiliar neighbors and beneath the shadow of the communist past. We longed to escape to a newly built single-family home with a garden and privacy.

Fast-forward two decades, and the trajectory inverted. The tiny local roads near our suburban house deteriorated under heavy traffic, while nearby green spaces were consumed by unchecked development. Meanwhile, Osiedle Widok quietly transformed into a thriving neighborhood: a car-limited zone with shops, playgrounds, excellent tram and bus connections, and strengthening, positive community ties. Now, families and young professionals actively choose it for the very qualities we once wanted to escape.

True, many of the original housing estates have real constraints. Small apartments, poor construction quality, and rigid design are genuine drawbacks. However, they were genuine necessities of a quickly modernizing economy with huge influx of people into the city. Something, we see another wave of today, and experience ourselves in micro-apartments proposed by developers.

local development plan "Nowa Huta Center", 2013

Osiedle Widok (in red) amid suburban sprawl. google earth engine timelapse shows decades of development encroachment.

The Reality of Urban Sustainability

Poland engineered functional 15-minute cities decades before the term entered global discourse, only to abandon them as relics of an unwanted past. Nowa Huta of the 1950s embodied principles we urgently need now: compact, walkable neighborhoods with integrated services and stable economic anchors.

Yet by dismissing these neighborhoods entirely, we've replaced one set of problems with another. Modern developers routinely sacrifice space and construction integrity in pursuit of margins while rarely considering the urban framework. Rather than demolishing the old, repurposing what remains becomes not just economically sensible but morally necessary—especially given that the building and construction sectors account for nearly 40% of global energy-related carbon emissions.

Two decades after leaving communal Osiedle Widok for suburban privacy, I find myself wondering: when I have my own family and am fortunate enough to choose, where would I rather live?

Perhaps the greatest innovation isn't designing new 15-minute cities—it's recognizing the ones we already built and moving beyond the assumption that everything socialist must be abandoned. In doing so, we don't return to communism; we simply acknowledge that good urban design transcends ideology, and that climate demands we stop confusing novelty with progress.

Bonus: Other 15-Minute City Neighborhoods in Poland

Ursynów, Warsaw (1970s–80s): The country's largest modernist housing estate, housing 150,000 residents, was designed with abundant green space and integrated schools, clinics, and commercial centers. It still maintains strong walkability and now ranks among Warsaw's most desirable districts, with property values exceeding the city average—proof that well-designed communist-era neighborhoods thrive when properly maintained.

Wrzeszcz, Gdańsk (Mixed Era): This district merges pre-war architecture with 1970s housing blocks. Rather than demolition, revitalization efforts focused on pedestrianization, cycling infrastructure, and public space improvements, preserving the functional urban fabric.

Giszowiec, Katowice (1907): This garden city predates socialist urban planning, demonstrating that proximity-based design can thrive across different political and economic systems. Designed by George and Emil Zillmann and inspired by Ebenezer Howard's garden city principles, it originally housed 600 families of coal miners with all necessary services clustered around a central marketplace.

What Is a 15-Minute City, Really?

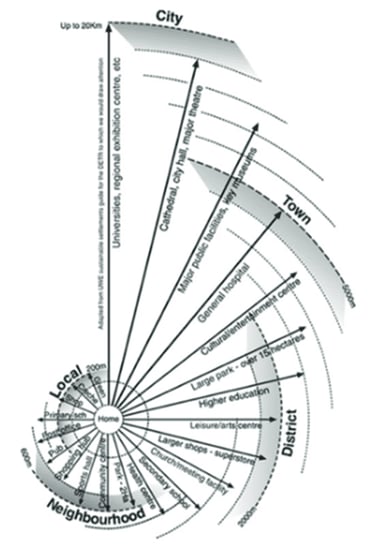

The term "15-minute city" entered mainstream discourse through urban theorist Carlos Moreno in 2016, but it's not always clear what constitutes one. Reaching back to early urban theorists of the 1960s, its foundational principles include:

Density: population concentration of 3,000–7,500 people per square kilometer sufficient to support local services

Diversity: mixed-use development rather than mono-functional zones—a good blend of housing, services, and workplaces

Design: featuring adequate pedestrian infrastructure, protected cycling lanes, and well-connected street networks

Recent research shows this isn't one-size-fits-all. Dense European city centers may achieve 15-minute accessibility primarily through walking, while in suburban areas, 20–30 minutes incorporating public transit represents a more realistic benchmark. The principle—enabling residents to meet daily needs through walkable, transit-connected neighborhoods—matters more than adherence to a precise duration.

Nowa Huta: The Old City of the Future

Nowa Huta, Kraków's easternmost district, was conceived in 1949 as a "socialist model city" for steelworkers, 75 years before the term "15-minute city" existed. Its main architect, Tadeusz Ptaszycki, drew inspiration from Renaissance urban ideals and Parisian boulevards. Which is ironic since he endeavored to align every aspect with anti-Western communist propaganda.

By design, Nowa Huta's sectors housed 4,000–5,000 residents each, complete with schools, shops, cultural centers, communal spaces, and abundant green areas. The result was a district with wide, hierarchical street structures radiating from a central plaza, rich tree canopies, and in-built self-sufficiency. Residents could meet all daily needs within walking distance - which is a 15-minute neighborhood, by definition.

But then things changed. Since it was built to house workers from the nearby Lenin Steelworks (now Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks, owned by ArcelorMittal), Nowa Huta lost its economic anchor when the plant drastically cut jobs after 1989 during the privatization spree. The district faced unemployment, poverty, and social problems, something that in Poland, we unkindly call patologia, loosely translating to "social pathology." Similar stories of decay can be found in other European post-industrial regions like Liverpool or the Ruhr Valley, not due to flawed urban design but the collapse of the economic systems they served.

After decades of neglect, Nowa Huta reinvented itself as one of Kraków's most desirable residential districts. Following revitalization initiatives, the district features modernized public spaces, wide green areas, and integrated public transit. Property investments and shifting housing preferences have reinforced this trajectory: large socialist neighborhoods now attract educated, professionally active residents and are increasingly seen as desirable. In 2020, The Guardian's readers ranked Nowa Huta as the top European neighborhood to visit.